By subverting the traditional role of gender in genre, Thelma & Louise (Scott, 1991) challenges traditional Hollywood gendered myths. An outline of gender will be provided before turning to Laura Mulvey’s ‘Visual Pleasures and Narrative Cinema’, which outlines how gender is traditionally perceived in the cinema. Applying her theories to Thelma & Louise it can be seen how the film attempts to reverse traditional gender roles, through the assumption of male agency, and the punishment of male characters. Thelma & Louise casts its female protagonists in a complex mix of traditionally masculine genres, but focus will be placed on the western and the road movie as a travel narrative. Both of these genres are thematically concerned with the myth of the frontier, which features ideas of wilderness, liberation, self-sufficiency, and therefore masculinity. The last part of the essay will be an exploration of the interaction of genre and gender. For example, how the western and road movie’s space and movement is traditionally gendered, how traditional gendered roles are reversed. Finally, gender and the use of violence in the film will be explored from a psychoanalytical perspective.

It could be argued that film traditionally reflects socially established interpretations of gender, but Thelma & Louise works to challenge these by ‘subverting the classical paradigms’ (Man, 1993, p.38). The ‘classical paradigm’ refers to the values, in a society that is shaped by culture and history, and is the most standard and widely held. The ideological function of gender is ‘to fix us as either male or female’ (Hayward, 2006, p.179). The essentialist approach places the sexes in binary oppositions, and the way that male and female is constructed is also made up of binary oppositions. For example, the female is ‘economically inferior to the male, is associated more with the domestic than the public sphere, and is more emotional’ (Hayward, 2006, p.179). The female is seen as passive and the male active.

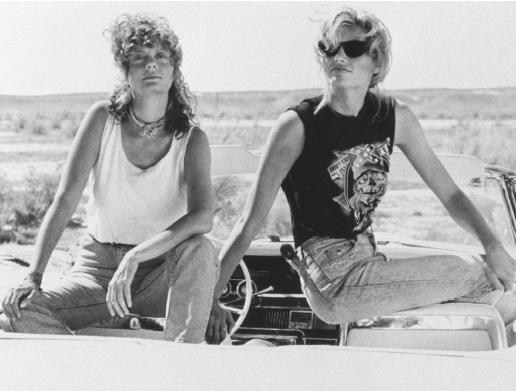

Mulvey argues that it is this ‘active/passive division of labour that has controlled narrative structure’ (Mulvey, 1988, p.63). The traditional role of women in the classical Hollywood paradigm has been that of a passive object, while the men are presented as active agents. The usurpation of the woman's body has been central to patterns of representation in cinema. As described in Mulvey's work, women are objectified and can be subject to what she refers to as the ‘male gaze’. However, limiting opportunities for women to be interpreted as erotic objects can prevent this. This peep-show gaze is made self-conscious in an early scene in Thelma & Louise; in the car Louise takes offense at Thelma's hiked dress revealing her thighs. Louise is more conscious of being objectified and does not wear any revealing clothes; her blouse is always buttoned to the top and her t-shirt loose fitting. The women actively prevent being viewed as erotic objects by concealing their sensuality.

For Thelma & Louise to subvert the classical Hollywood paradigm, the narrative has to show a character development from passive female subject to active female agent. The opening scenes of the film place Thelma and Louise in their female spheres, Louise working as a waitress at a diner, and Thelma a subservient housewife. Although they subvert the expectation of male discourse by deserting their men for a weekend, their actions ‘reflect not so much their independence as their ties to a system in which marriage plays an essential role’ (Man, 1993, p.40). Louise’s motive for the trip is to shock her partner into a firmer commitment, and Thelma makes sure she leaves a note and dinner in the microwave. Once they leave their home and community for the expanse of the open road events conspire to alter their characters. ‘The catalyst for the women’s rebellion is Thelma’s near rape’ (Man, 1993, p.40), and it is the would-be rapist attitude that triggers Louise’s reaction. What follows is a shift from on the road to on the run, as the violence from man incites violence to man. The freedom of the open road allows ‘a playing out of different roles, and ultimately shedding one’s old identity for a new one’ (Chumo II, 1991, p.24).

Louise could be considered masculine, as she is the more independent of the two, living alone and working. In one of the first scenes, where Thelma and Louise are talking on the telephone, Thelma tells Louise that her husband, Darryl “already thinks you’re a man”. Thelma, inspired by Louise’s action, throws off her passive resignation, attains sexual liberation, and turns her back on her former life with her unappreciative husband. The character of J.D. is a hitchhiker that is picked up by the women. After a sexual encounter with Thelma he robs the women and therefore could be viewed as a tool of classical narration that must punish female agency, however, he does function to empower the two women. Thelma attains sexual liberation with J.D. and after their encounter states “I finally understand what all the fuss is about”. He also enables her to adopt a dominant male role when she robs the liquor store at gunpoint just as he demonstrated for her. Thelma therefore attains liberation and growth through role-play and her search for self-identity ‘includes the incorporation of J.D.’s discourse into her own’ (Man, 1993, p.41).

There are various representations of men throughout the film; Thelma’s husband is portrayed as an unappreciative, chauvinistic and a slob, Jimmy, Louise’s partner, is only ready for a commitment when he fears he may be losing Louise. The men remain in the domestic sphere with the women no longer there to aid them. Free from their male-centred lives and in possession of a new independent identity, the women reject and ‘extricate themselves from the subservient formulations within male narratives’ (Man, 1993, p.42). The liberated women subject the other male characters to humiliation; a lewd truck driver finally receives his comeuppance when Thelma and Louise open fire on his tanker truck. This truck resembles a silver bullet, which was the name of the bar where Thelma was attacked; this is perhaps employed as a marker for the development of the women from passive victims. When the women encounter a state trooper Thelma pulls out her gun, and the trooper is reduced to tears. He states he has a wife and kids and she replies “You be sweet to them, especially your wife. My husband wasn’t sweet to me. Look how I turned out”, highlighting the theory that Thelma’s violence is a result of male oppression.

On the run, Thelma and Louise take over the dominant roles normally assigned to men, Thelma’s liquor store robbery and Louise’s revenge unleashed on the rapist ‘punctuate their assumption of male agency’ (Man, 1993, p.40). They resist to the end the temptation of compromise, and therefore reintegration into patriarchal society. By the time of their ‘grand suicidal leap into that great vaginal wonder of the world’ (`Kinder, 1991, p.30), the woman’s paraphernalia associated with the spectacled woman, such as the headscarf worn to keep their hair neat, sunglasses and lipstick, has worn away. As the car flies off the cliff a Polaroid of the women at the beginning of the trip flits away, now just ‘a flimsy reminder of the women’s past identities’ (Man, 1993, p.41).

Thelma & Louise ‘incorporation of Hollywood genres into its discourse further complicates its process of challenging the classical paradigm’ (Man, 1993, p.42). It could be argued that the film both subverts generic conventions, and includes them in a complex mixture of references. Critical debate has found the film’s genre contentious, as elements of the western, road movie, screwball comedy, gangster film, and melodrama can be found within the film, which creates a ‘strange generic mix’ (Welsh, 2009, p.215).

Most of the film’s critical debate has been focused around the western and the road film when analysing Thelma & Louise. Although there are problems associated with clear definitions of genres, it is generally believed that location and iconography such as setting, costume, and stars places the western in a category of its own. Iconography has received particular attention because it was ‘felt to be concerned specifically with the role of the visual in genre films’ (Neale, 2003, p.10), the visual being distinct and assessable. Douglas Pye states that in the Western, iconography ‘would include landscape, architecture, modes of transport, weapons and clothes’ (2003, p.206). In Thelma & Louise the mise-en-scene of the western has been updated, the costumes, weapons, landscape, and modes of transport remain, but all are given a contemporary twist. For example, the costumes and weapons are appropriated by both the sexes, and the landscape features a snaking road to enable the change of vehicle from horseback to automobile.

Thelma and Louise’s chase is played out against the familiar landscape of the western. The opening shot of the film is an open road stretching out into the desert towards the mountains, which is ‘iconic of both the road movie and the western and encourages particular generic expectations’ (Welsh, 2009, p.215). It suggests not just the wide-open spaces of the ‘American West’ but the freedom and self-determination of the myth of ‘the West’ popularised by Hollywood. The opening shot turns from black and white to colour; perhaps signifying an update from an old genre to a new revised one.

It could be argued that the iconography of the western bleeds over into the road movie. As the western frequently features a travel narrative, the road movie could be considered a contemporary western. The travel narrative features themes of individualism and ‘sets the liberation of the road against the oppression of hegemonic norms, road movies project American Western mythology’ (Cohan and Hark, 1997, p.1). Linking a town and country, the road forges through an empty expanse that could be considered the last frontier. The frontier symbolism inherent in both the Western and the road movie features conception of American national identity that revolves around individualism. Like the western, road movies romanticise alienation and an escape from civilised life, escaping the constraints of society for the freedom of the open road. Both the western and the road movie create a pattern of individualism vs. integration in a conflict between wilderness and civilised values, which ‘provide the traditional thematic structure of the genre’ (Kitses, 2004, p.11). Man claims that in the western this conflict is often ‘internalised with the western hero’ (Man, 1993, p.43) who works with the community in an expansion of civilisation but the retreats into the wilderness to preserve his individualism. Thelma & Louise ‘performs a sex change on Western mythology (Kinder, 1991, p.30).

Neale’s essay on the relationship between genre and sexuality outlines that genre maintains sexual difference, and creates an ‘ongoing process of construction of sexual difference and sexual identity’ (1980, p.56), this can be achieved by looking at a genre’s location. An audience familiar with traditional Hollywood films would be aware that spaces are gendered: in both the road movie and the western’ the open road and the frontier ‘is a predominately ‘male’ space’ (Welsh, 2009, p.215). However, it could also be argued that movement itself is gendered. The travel narrative is defined by men on the move, while melodrama, considered a feminine genre is often defined by its domesticity, and does not usually feature any significant geographical movement. It is the western’s setting that creates the genre’s basic masculine conventions, such as the wandering life, lawlessness leading to violence, and freedom from the constraints of society. Kitses’ elements separating the wilderness and civilisation highlight how the setting of the western creates a structure that is ‘concerned with making the man’ (2004, p.18), as the wilderness is considered a masculine space and civilisation a female one.

However, the western is also defined by its mise-en-scene and this allows filmmakers freedom to explore different themes. Kitses remarks rather elegantly that the western ‘is an empty vessel breathed into by the filmmaker, the genre is a vital structure through which flow a myriad of themes and concepts’ (2004, p.10). Therefore, a reversal of gender roles is feasible in Thelma & Louise without disrupting the references to the western. As western heroines, Thelma and Louise ‘appropriate the function of the male’ (Man, 1993, p.45). In a reversal of male and female spheres they ride the open road, stage robberies and shoot the villain while their men stay at home. To be successful on the open road Thelma and Louise must take on masculine attributes. It could also be argued that J.D. ‘plays the seducer and thief that gives and betrays as well as any femme fatale ever managed to do’ (Boozer, 1995, p.194). Resembling James Dean, the camera lingers on his toned torso perhaps to suggest that he is the film’s ‘sex symbol’ (Johnson, 1991, p.23) rather than the women that he seduces. Therefore we could also look at the character of J.D. as a reversal of the gender roles.

Greenberg highlights that the mix of genre and gender in the film is paradoxical and addresses ‘differing ideological agendas; the feminist, and antifeminist’ (Man, 1993, p.36). Therefore, the film can either be interpreted as a feminist manifesto, portraying ordinary women driven to desperate ends by the oppression of men, or as anti feminist, with heroines that are dangerous ‘caricatures of the very macho violence that they’re supposed to be protecting’ (Greenberg, 1991, p.20). Although the use of violence in the film may have created debate, it could be seen to challenge traditional gender roles.

Looking at a film’s gender from a psychoanalytical perspective, protagonists often become either objects of identification or objects of desire. The western hero is normally seen as an object of identification, but much debate has surrounded the idea of the male representing an object of desire. Neale argued that ‘both the female and the male body can be situated as spectacle in the scopic drive (1980, p.56). Repression is required to dispel this, so images of masculinity are juxtaposed with images of violence. Sadism is active, it demands a story, depends on making something happen, and forces a change in a person (Mulvey, 1988, p.64). In the case of Thelma & Louise, it may be the violent treatment that Thelma receives at the Silver Bullet and the heroism of Louise that enables the audience to identify and care for the characters.

However, Thelma & Louise has been criticised for behaving, in ‘the tradition of most American heroes, violently without reflection (Williams, 1991, p.27). Male critics have been especially critical claiming that the film is ’nihilistic, “toxic feminism” with a fascist theme’ (Williams, 1991, p.27). Yet, just as the sadistic treatment of men can create identification for male audiences through trial, the same not work for women? The violence in the film may have been essential to change audiences’ perceptions of the women and challenge the classical paradigms. By creating a reversal of gender in a traditionally masculine genre, Thelma & Louise succeeds in creating contestation across the political spectrum, but also lays bare ‘the violence and brutality under the celluloid-thin myths of self-sufficiency and heroism’ (Braudy 1991, p. 28).

In conclusion, the masculine genres featured in this film are proved to be malleable when a reversal of gender takes place. In exposing the construction of the genre Thelma & Louise creates a process of revision. Escaping the trappings of female civilisation and domesticity, the women take on the male frontier values of individualism and self-reliance. The women escape conflict and oppression, but they do not overcome it. They may embrace their new masculine identity, but their death indicates that there is not a place in a patriarchal society for their hybridity. Looking at the use of violence from a psychoanalytical position may suggest that it is necessary for the development of a relationship between character and audience. However, switching the gender of those acting out violence has created wide debate both for and against, even though the same violence is traditionally acceptable when played out by a male protagonist. This serves to highlight that there are still certain conventions of gender construction that Thelma & Louise could not overcome.

2698 words

Boozer, J. (1995). Seduction and betrayal in the heartland: Thelma and Louise. Literature Film Quarterly, Vol. 23(3), 188-196.

Cohan, S., Hark, I. N., et al. (1997). The Road Movie Book. London: Routledge.

Greenberg, H. R., Clover, C. J., Johnson, A., Chumo II, P. N., Henderson, B., Williams, L., Kinder, M., Braudy, L., et al. (1991). The Many faces of Thelma and Louise. Film Quarterly, 45(2), 20-31.

Hayward, S. (2006). Cinema Studies, The Key Concepts (3rd Ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

Kitses, J. (2004). Horizons West: Directing the western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. London: BFI Publishing.

Man, G. (1993). Gender, Genre, and Myth in Thelma and Louise. Film Criticism, 18(1), 36-53.

Mulvey, L. (1988). Visual Pleasures and Narrative Cinema. In C. Penley (Ed.), Feminism and Film Theory (pp.57-68). London: BFI Publishing.

Neale, S. (2003). Genre. London: BFI Publishing.

Pye, D. (2003). The Western (Genre and Movies). In B. K. Grant (Eds.), Film Genre Reader III. (pp. 203-218). Austin: University of Texas.

Scott, R. (Director). (1991). Thelma & Louise [Motion Picture]. USA: Pathé Entertainment Inc / Percy Main / Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Tudor, A. (1974). Theories of Film. In B. K. Grant (Eds.), Film Genre Reader III. (pp. 3-11). Austin: University of Texas.

Welsh, J. (2009). Thelma and Louise. In J. White & S. Haenni (Eds.), Fifty Key American Films. (pp.213-218). London: Routledge.