a secret public diary

About Me

- a secret public diary

- the inner ramblings and essays of a film student that's looking for the thrill of sharing with the unknown.

Monday, 28 November 2011

Friday, 4 February 2011

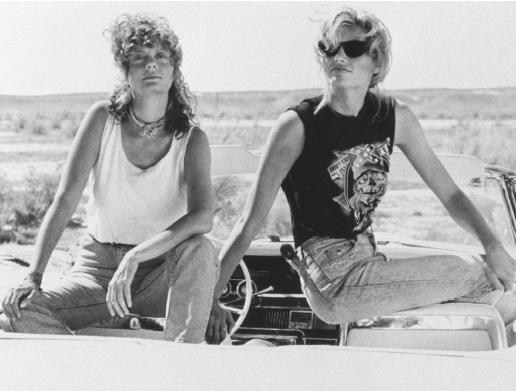

The interplay of Gender and Genre in Thelma & Louise

By subverting the traditional role of gender in genre, Thelma & Louise (Scott, 1991) challenges traditional Hollywood gendered myths. An outline of gender will be provided before turning to Laura Mulvey’s ‘Visual Pleasures and Narrative Cinema’, which outlines how gender is traditionally perceived in the cinema. Applying her theories to Thelma & Louise it can be seen how the film attempts to reverse traditional gender roles, through the assumption of male agency, and the punishment of male characters. Thelma & Louise casts its female protagonists in a complex mix of traditionally masculine genres, but focus will be placed on the western and the road movie as a travel narrative. Both of these genres are thematically concerned with the myth of the frontier, which features ideas of wilderness, liberation, self-sufficiency, and therefore masculinity. The last part of the essay will be an exploration of the interaction of genre and gender. For example, how the western and road movie’s space and movement is traditionally gendered, how traditional gendered roles are reversed. Finally, gender and the use of violence in the film will be explored from a psychoanalytical perspective.

It could be argued that film traditionally reflects socially established interpretations of gender, but Thelma & Louise works to challenge these by ‘subverting the classical paradigms’ (Man, 1993, p.38). The ‘classical paradigm’ refers to the values, in a society that is shaped by culture and history, and is the most standard and widely held. The ideological function of gender is ‘to fix us as either male or female’ (Hayward, 2006, p.179). The essentialist approach places the sexes in binary oppositions, and the way that male and female is constructed is also made up of binary oppositions. For example, the female is ‘economically inferior to the male, is associated more with the domestic than the public sphere, and is more emotional’ (Hayward, 2006, p.179). The female is seen as passive and the male active.

Mulvey argues that it is this ‘active/passive division of labour that has controlled narrative structure’ (Mulvey, 1988, p.63). The traditional role of women in the classical Hollywood paradigm has been that of a passive object, while the men are presented as active agents. The usurpation of the woman's body has been central to patterns of representation in cinema. As described in Mulvey's work, women are objectified and can be subject to what she refers to as the ‘male gaze’. However, limiting opportunities for women to be interpreted as erotic objects can prevent this. This peep-show gaze is made self-conscious in an early scene in Thelma & Louise; in the car Louise takes offense at Thelma's hiked dress revealing her thighs. Louise is more conscious of being objectified and does not wear any revealing clothes; her blouse is always buttoned to the top and her t-shirt loose fitting. The women actively prevent being viewed as erotic objects by concealing their sensuality.

For Thelma & Louise to subvert the classical Hollywood paradigm, the narrative has to show a character development from passive female subject to active female agent. The opening scenes of the film place Thelma and Louise in their female spheres, Louise working as a waitress at a diner, and Thelma a subservient housewife. Although they subvert the expectation of male discourse by deserting their men for a weekend, their actions ‘reflect not so much their independence as their ties to a system in which marriage plays an essential role’ (Man, 1993, p.40). Louise’s motive for the trip is to shock her partner into a firmer commitment, and Thelma makes sure she leaves a note and dinner in the microwave. Once they leave their home and community for the expanse of the open road events conspire to alter their characters. ‘The catalyst for the women’s rebellion is Thelma’s near rape’ (Man, 1993, p.40), and it is the would-be rapist attitude that triggers Louise’s reaction. What follows is a shift from on the road to on the run, as the violence from man incites violence to man. The freedom of the open road allows ‘a playing out of different roles, and ultimately shedding one’s old identity for a new one’ (Chumo II, 1991, p.24).

Louise could be considered masculine, as she is the more independent of the two, living alone and working. In one of the first scenes, where Thelma and Louise are talking on the telephone, Thelma tells Louise that her husband, Darryl “already thinks you’re a man”. Thelma, inspired by Louise’s action, throws off her passive resignation, attains sexual liberation, and turns her back on her former life with her unappreciative husband. The character of J.D. is a hitchhiker that is picked up by the women. After a sexual encounter with Thelma he robs the women and therefore could be viewed as a tool of classical narration that must punish female agency, however, he does function to empower the two women. Thelma attains sexual liberation with J.D. and after their encounter states “I finally understand what all the fuss is about”. He also enables her to adopt a dominant male role when she robs the liquor store at gunpoint just as he demonstrated for her. Thelma therefore attains liberation and growth through role-play and her search for self-identity ‘includes the incorporation of J.D.’s discourse into her own’ (Man, 1993, p.41).

There are various representations of men throughout the film; Thelma’s husband is portrayed as an unappreciative, chauvinistic and a slob, Jimmy, Louise’s partner, is only ready for a commitment when he fears he may be losing Louise. The men remain in the domestic sphere with the women no longer there to aid them. Free from their male-centred lives and in possession of a new independent identity, the women reject and ‘extricate themselves from the subservient formulations within male narratives’ (Man, 1993, p.42). The liberated women subject the other male characters to humiliation; a lewd truck driver finally receives his comeuppance when Thelma and Louise open fire on his tanker truck. This truck resembles a silver bullet, which was the name of the bar where Thelma was attacked; this is perhaps employed as a marker for the development of the women from passive victims. When the women encounter a state trooper Thelma pulls out her gun, and the trooper is reduced to tears. He states he has a wife and kids and she replies “You be sweet to them, especially your wife. My husband wasn’t sweet to me. Look how I turned out”, highlighting the theory that Thelma’s violence is a result of male oppression.

On the run, Thelma and Louise take over the dominant roles normally assigned to men, Thelma’s liquor store robbery and Louise’s revenge unleashed on the rapist ‘punctuate their assumption of male agency’ (Man, 1993, p.40). They resist to the end the temptation of compromise, and therefore reintegration into patriarchal society. By the time of their ‘grand suicidal leap into that great vaginal wonder of the world’ (`Kinder, 1991, p.30), the woman’s paraphernalia associated with the spectacled woman, such as the headscarf worn to keep their hair neat, sunglasses and lipstick, has worn away. As the car flies off the cliff a Polaroid of the women at the beginning of the trip flits away, now just ‘a flimsy reminder of the women’s past identities’ (Man, 1993, p.41).

Thelma & Louise ‘incorporation of Hollywood genres into its discourse further complicates its process of challenging the classical paradigm’ (Man, 1993, p.42). It could be argued that the film both subverts generic conventions, and includes them in a complex mixture of references. Critical debate has found the film’s genre contentious, as elements of the western, road movie, screwball comedy, gangster film, and melodrama can be found within the film, which creates a ‘strange generic mix’ (Welsh, 2009, p.215).

Most of the film’s critical debate has been focused around the western and the road film when analysing Thelma & Louise. Although there are problems associated with clear definitions of genres, it is generally believed that location and iconography such as setting, costume, and stars places the western in a category of its own. Iconography has received particular attention because it was ‘felt to be concerned specifically with the role of the visual in genre films’ (Neale, 2003, p.10), the visual being distinct and assessable. Douglas Pye states that in the Western, iconography ‘would include landscape, architecture, modes of transport, weapons and clothes’ (2003, p.206). In Thelma & Louise the mise-en-scene of the western has been updated, the costumes, weapons, landscape, and modes of transport remain, but all are given a contemporary twist. For example, the costumes and weapons are appropriated by both the sexes, and the landscape features a snaking road to enable the change of vehicle from horseback to automobile.

Thelma and Louise’s chase is played out against the familiar landscape of the western. The opening shot of the film is an open road stretching out into the desert towards the mountains, which is ‘iconic of both the road movie and the western and encourages particular generic expectations’ (Welsh, 2009, p.215). It suggests not just the wide-open spaces of the ‘American West’ but the freedom and self-determination of the myth of ‘the West’ popularised by Hollywood. The opening shot turns from black and white to colour; perhaps signifying an update from an old genre to a new revised one.

It could be argued that the iconography of the western bleeds over into the road movie. As the western frequently features a travel narrative, the road movie could be considered a contemporary western. The travel narrative features themes of individualism and ‘sets the liberation of the road against the oppression of hegemonic norms, road movies project American Western mythology’ (Cohan and Hark, 1997, p.1). Linking a town and country, the road forges through an empty expanse that could be considered the last frontier. The frontier symbolism inherent in both the Western and the road movie features conception of American national identity that revolves around individualism. Like the western, road movies romanticise alienation and an escape from civilised life, escaping the constraints of society for the freedom of the open road. Both the western and the road movie create a pattern of individualism vs. integration in a conflict between wilderness and civilised values, which ‘provide the traditional thematic structure of the genre’ (Kitses, 2004, p.11). Man claims that in the western this conflict is often ‘internalised with the western hero’ (Man, 1993, p.43) who works with the community in an expansion of civilisation but the retreats into the wilderness to preserve his individualism. Thelma & Louise ‘performs a sex change on Western mythology (Kinder, 1991, p.30).

Neale’s essay on the relationship between genre and sexuality outlines that genre maintains sexual difference, and creates an ‘ongoing process of construction of sexual difference and sexual identity’ (1980, p.56), this can be achieved by looking at a genre’s location. An audience familiar with traditional Hollywood films would be aware that spaces are gendered: in both the road movie and the western’ the open road and the frontier ‘is a predominately ‘male’ space’ (Welsh, 2009, p.215). However, it could also be argued that movement itself is gendered. The travel narrative is defined by men on the move, while melodrama, considered a feminine genre is often defined by its domesticity, and does not usually feature any significant geographical movement. It is the western’s setting that creates the genre’s basic masculine conventions, such as the wandering life, lawlessness leading to violence, and freedom from the constraints of society. Kitses’ elements separating the wilderness and civilisation highlight how the setting of the western creates a structure that is ‘concerned with making the man’ (2004, p.18), as the wilderness is considered a masculine space and civilisation a female one.

However, the western is also defined by its mise-en-scene and this allows filmmakers freedom to explore different themes. Kitses remarks rather elegantly that the western ‘is an empty vessel breathed into by the filmmaker, the genre is a vital structure through which flow a myriad of themes and concepts’ (2004, p.10). Therefore, a reversal of gender roles is feasible in Thelma & Louise without disrupting the references to the western. As western heroines, Thelma and Louise ‘appropriate the function of the male’ (Man, 1993, p.45). In a reversal of male and female spheres they ride the open road, stage robberies and shoot the villain while their men stay at home. To be successful on the open road Thelma and Louise must take on masculine attributes. It could also be argued that J.D. ‘plays the seducer and thief that gives and betrays as well as any femme fatale ever managed to do’ (Boozer, 1995, p.194). Resembling James Dean, the camera lingers on his toned torso perhaps to suggest that he is the film’s ‘sex symbol’ (Johnson, 1991, p.23) rather than the women that he seduces. Therefore we could also look at the character of J.D. as a reversal of the gender roles.

Greenberg highlights that the mix of genre and gender in the film is paradoxical and addresses ‘differing ideological agendas; the feminist, and antifeminist’ (Man, 1993, p.36). Therefore, the film can either be interpreted as a feminist manifesto, portraying ordinary women driven to desperate ends by the oppression of men, or as anti feminist, with heroines that are dangerous ‘caricatures of the very macho violence that they’re supposed to be protecting’ (Greenberg, 1991, p.20). Although the use of violence in the film may have created debate, it could be seen to challenge traditional gender roles.

Looking at a film’s gender from a psychoanalytical perspective, protagonists often become either objects of identification or objects of desire. The western hero is normally seen as an object of identification, but much debate has surrounded the idea of the male representing an object of desire. Neale argued that ‘both the female and the male body can be situated as spectacle in the scopic drive (1980, p.56). Repression is required to dispel this, so images of masculinity are juxtaposed with images of violence. Sadism is active, it demands a story, depends on making something happen, and forces a change in a person (Mulvey, 1988, p.64). In the case of Thelma & Louise, it may be the violent treatment that Thelma receives at the Silver Bullet and the heroism of Louise that enables the audience to identify and care for the characters.

However, Thelma & Louise has been criticised for behaving, in ‘the tradition of most American heroes, violently without reflection (Williams, 1991, p.27). Male critics have been especially critical claiming that the film is ’nihilistic, “toxic feminism” with a fascist theme’ (Williams, 1991, p.27). Yet, just as the sadistic treatment of men can create identification for male audiences through trial, the same not work for women? The violence in the film may have been essential to change audiences’ perceptions of the women and challenge the classical paradigms. By creating a reversal of gender in a traditionally masculine genre, Thelma & Louise succeeds in creating contestation across the political spectrum, but also lays bare ‘the violence and brutality under the celluloid-thin myths of self-sufficiency and heroism’ (Braudy 1991, p. 28).

In conclusion, the masculine genres featured in this film are proved to be malleable when a reversal of gender takes place. In exposing the construction of the genre Thelma & Louise creates a process of revision. Escaping the trappings of female civilisation and domesticity, the women take on the male frontier values of individualism and self-reliance. The women escape conflict and oppression, but they do not overcome it. They may embrace their new masculine identity, but their death indicates that there is not a place in a patriarchal society for their hybridity. Looking at the use of violence from a psychoanalytical position may suggest that it is necessary for the development of a relationship between character and audience. However, switching the gender of those acting out violence has created wide debate both for and against, even though the same violence is traditionally acceptable when played out by a male protagonist. This serves to highlight that there are still certain conventions of gender construction that Thelma & Louise could not overcome.

2698 words

Boozer, J. (1995). Seduction and betrayal in the heartland: Thelma and Louise. Literature Film Quarterly, Vol. 23(3), 188-196.

Cohan, S., Hark, I. N., et al. (1997). The Road Movie Book. London: Routledge.

Greenberg, H. R., Clover, C. J., Johnson, A., Chumo II, P. N., Henderson, B., Williams, L., Kinder, M., Braudy, L., et al. (1991). The Many faces of Thelma and Louise. Film Quarterly, 45(2), 20-31.

Hayward, S. (2006). Cinema Studies, The Key Concepts (3rd Ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

Kitses, J. (2004). Horizons West: Directing the western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. London: BFI Publishing.

Man, G. (1993). Gender, Genre, and Myth in Thelma and Louise. Film Criticism, 18(1), 36-53.

Mulvey, L. (1988). Visual Pleasures and Narrative Cinema. In C. Penley (Ed.), Feminism and Film Theory (pp.57-68). London: BFI Publishing.

Neale, S. (2003). Genre. London: BFI Publishing.

Pye, D. (2003). The Western (Genre and Movies). In B. K. Grant (Eds.), Film Genre Reader III. (pp. 203-218). Austin: University of Texas.

Scott, R. (Director). (1991). Thelma & Louise [Motion Picture]. USA: Pathé Entertainment Inc / Percy Main / Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Tudor, A. (1974). Theories of Film. In B. K. Grant (Eds.), Film Genre Reader III. (pp. 3-11). Austin: University of Texas.

Welsh, J. (2009). Thelma and Louise. In J. White & S. Haenni (Eds.), Fifty Key American Films. (pp.213-218). London: Routledge.

Memory - Amnesia (1994) & La Finestra di Fronte (2004)

This essay will explore how memory is essential in the formation of identity, how national identity could be labelled a national interest, and how these themes are represented in the films Amnesia (Justiniano, 1994) and La Finestra Di Fronte (Özpetek, 2004). An overview of the discourses surrounding national interest and memory will be provided, followed by an analysis of the film Amnesia. This will focus on the representation of several of the film’s characters that symbolise different fractions of Chilean society and the cinematic techniques used to link the past with contemporary national interests. An analysis of La Finestra Di Fronte will also be provided focusing on the merging of past and present, the character of Davide, and the representation of his memories. This essay will argue that Davide's traumatic past and Giovanna’s ignorance are representative of the nation, that cinema aids in the mediation of memory, and that memory’s repression or acknowledgment is a national interest as it effects the national identity.

The term national interest could be considered ambiguous. David Clinton offers the definition that it ‘lies in the obligation to protect and promote the good of society’ (Clinton, 1994, p.52). Its ambiguity lies in the fact that common good has to be assessed, and it could therefore have several possible meanings or interpretations. National interest has been labelled undemocratic as it ‘can be used as a convenient and often convincing cover for the machinations of self interested groups, (…) and for the suppression of dissenting groups’ (Clinton, 1994, p.72). However, national interest can also stand for the protection of what holds society together as a community, a unification that requires common interests and the formation of common identity. But this also requires a level of control and there is a danger of irresponsible power inherent in it.

Both of the films this essay will analyse feature the theme of memory, which has also been related to operations of power. Memory is socially produced and intrinsically linked to the formation of identity. Michel Foucault stated that ‘if one controls people’s memory, one controls their dynamism’ (Foucault, 1996, p.124). Memory can be as much collective as individual, as individual memories can be incomplete and fragmented. Completion of these memories can be sought ‘in the social world outside the individual’ (Storey, 2003, p.101), but this also suggests that they are open to manipulation. As memory is such an important factor in construction of identity, either individual or collective, it can be used as a political force and could be labelled as a national interest.

However, memories do not just consist of what has been remembered, but what has been forgotten. The Chilean film Amnesia features flashbacks to the country’s recent past, under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. Only in 1990 did Chileans begin to again elect their political leaders, after a 17-year military dictatorship. Chileans living under this regime were unable to make films addressing contemporary issues, and at the end of the regime Pinochet publicly called for the nation to forget the past. Cultivated under a political consensus, the government persuaded the public that to it was in the national interest to forget.

The character of Ramírez highlights the importance of reclaiming memory not just on an individual level, but a national level as well. It could be argued that he is representative of the general population of Chile, as he is placed as a neutral figure between the guards of the camp and the prisoners themselves, just as the general population of Chile would have been placed between the state and dissenting groups. Suffering from amnesia he is obsessively searching for his former sergeant, and ‘it appears he is unable to function in the present until he begins to explore his past’ (Shaw, 2003, p.76). When looking at his reflection on a shiny plate in the opening sequence, his image is distorted and he is unable to recognise himself. We could take this image of distortion as symbolising his mind and his identity. It is only when he meets Zúñiga again that his memories start to return. The flashbacks are shown in a linear development and through them Ramírez, and the audience, are able to make sense of his past, and the trauma he has been through. If Ramírez is representative of society, then his story suggests that reclaiming the nation’s collective memory is essential if the nation is to construct a better future.

The other central characters could be argued to represent the opposing groups in society. Alvear is one of the prisoners at the camp, his journal and words are ‘repeated by Mandiola, and reread by Ramírez’ (Shaw, 2003, p.79) to create a counter-history. Alvear states, “These signs are the only testimony repeated by the mouths of the dead”. By choosing to present Alvear, a victim of the regime, the film gives back those murdered a voice, by presenting their lost testimonies. Sergeant Zúñiga is also suffering from amnesia, but unlike Ramírez his amnesia is self-regulated, and an attempt to protect himself from his conscience. Zúñiga echoes Pinochet and tells Ramírez to “forget the past”. However, his trial by Ramírez and Carrasco at the end could be representative of the military regime, all those that followed orders and committed crimes, and his guilt becomes their guilt. Zúñiga and Alvear, channelling the voices of the dead, and the dictator himself, represent the polar opposites of the regime.

It could be argued that the film uses the past to comment directly on ‘the principle political and social issues confronting contemporary Chileans’ (Shaw, 2003, p.73). The use of the flashback means that the film is not set in the past but in the present, so the relationship between the two is central in the audience’s mind. The film features many symbols that represent a close connection between the two times, such as the use of match on action editing and the images of swinging lamps in the present, and in the past. Flashbacks could also represent collective memory as they ‘give us images of history, the shared and recorded past’ (Turim, 1989, p.2). The flashbacks could be interpreted as a mixture of both Zúñiga’s and Ramírez’s memories. Depicting scenes in which Ramírez is not present, the audience becomes aware that they are not shot within any one character’s subjective view, but that the camera takes on the role of a third-person omniscient narrator. Therefore, the use of flashbacks highlights that memory can be collective and is linked to the present. Through visual representations of memory, the film ‘effectively challenges official rejections of the past’ (Shaw, 2003, p.77). It is dependent on flashbacks for meaning and this way parallels the countries need to analyse its nation’s history. Like the narrative of Ramírez, the film could suggest that it is a national interest to end an officially endorsed amnesia, and that this would enable the country to recover from the traumas of the dictatorship.

Like Amnesia, La Finestra di Fronte also employs the use of flashback as a tool to link the past with the present. It deals with themes of amnesia, and features flashbacks to Nazi persecution in Italy. The film begins in 1940s Rome with a murder and the perpetrator leaving a bloody handprint on a wall. Time is sped up to show the handprint gradually disappearing then the camera pans away to show us that the film is now set in the current day. A small trace is still visible and it could be argued that this is a representation of how ‘the past still marks the future’ (Marcus, 2007, p.142).

The film uses the character of Davide to comment on the country’s denial of history and the importance of passing on memory. Davide, like Ramirez, is unable to make sense of the present without his memories, but unlike Ramírez, Davide’s memory needs reordering rather than reclaiming. His flashbacks are portrayed as subjective and do not have order or a linear narrative. They often appear as visions and sounds superimposed on modern day Rome, such the sound of marching, and a little girl confronting him in the street. It seems as if Davide’s past haunts him and his memories appear as ghosts. The disturbances of Davide’s fragmented mind could be caused by the unhealthy repression of traumatic events. Davide is lost in Rome, and it could be argued that representing him as a confused old man without a name highlights how important memories are in the formation of identity. Giovanna and Filippo take him into their home and attempt to discover who he is, and as his past is excavated we uncover ‘a lost 1940s history of racial and sexual persecution’ (Wood, 2005, p.214). Only by retelling is Davide able to reassess and reorder his memories, but to do so he must have a listener. Giovanna becomes the necessary ‘addressable other’ in the film and represents a new generation of witness. It is only when Davide able to pass on his testimony that the audience is given a linear retelling of events. The film suggests that passing on memory is essential in the formation of a country’s identity.

Contemporary Italy, as represented in the film, is utterly devoid of historical memory, and Giovanna’s ‘historical obliviousness exemplifies that of an entire generation living in the eternal present of contemporary media culture’ (Marcus, 2007, p.142). Giovanna and her family are unaware of their country’s traumatic past and Davide’s testimony is passed on to them. A family is considered a micro-community that could be representative of society. By using the family ‘public and political is presented through the private sphere of human feelings, memories, love and regrets’ (Laviosa, 2005, p.213). In this way it could be argued that the private and personal represents the public and political. Davide’s story is politicised; his history becomes his country’s history and the family becomes contemporary Italy.

There are other forces aside from political within the negotiation of memory. Cinema is a powerful medium that represents and embodies the past like no other; therefore ‘it has become essential to the mediation of memory in modern cultural life’ (Grainge, 2003, p.1). Özpetek invokes the past with the casting of Massimo Girotti, a ‘personification of post-war Italian film history’ (Marcus, 2007, p.143) for the character of Davide. In the wake of fascism and war there was a need to redefine national identity, ‘which produced a stylistically and philosophically distinctive cinema’ (Shiel, 2006, p.1). By casting Girotti it could be argued that Özpetek is bringing the history of Italy’s committed art with the most solemn act that a historical reconstruction can perform – that of bearing witness (Marcus, 2002, p.267).

La Finestra di Fronte directly confronts problems of historical trauma and its ‘effects on the Italian collective psyche as it struggles to come to terms with the past’ (Marcus, 2007, p.145). Davide is at the end of his life and his character is the sum of its experience, not one that will be able to develop or change. He cannot go back and change his decision to save the ghetto rather than his lover Simone. The past is a fixed moment and events cannot alter, ‘the potential for evolution and change, for enactive access of any sort is negated’ (Hope, 2005, p.58). He tells Giovanna “I can’t do anything anymore. But you… you still have a choice. You can change Giovanna.” Giovanna’s gains courage from Davide’s story to change her life. She asks “Does everyone who leaves you always leave a part of themselves with you? Is that the secret of having memories?” Giovanna inherits Davide’s memory and he continues to live through her. In Giovanna’s letter to Davide at the end of the film she says that her daughter Martina still asks about him and “I’ll tell her your story”. This confirms that the testimony will be passed on to future generations as well. The film suggests that memories are transferable, effect identity, and that the nation has much to gain by acknowledging and mourning their traumatic past. In this way it represents the importance of making memory a national interest.

Both of the countries analysed use amnesia to deal with their fascist past, but both of the films analysed challenge this amnesia and demonstrate the importance of acknowledging history. The personal memory of Ramirez and Davide is representative of their country’s collective memory, and just as memory effects individual identity it can also aid in the formation of a national identity. Therefore, it could be argued that memory is used as a central theme in both of these films to highlight its power, and that memory is represented as a key national interest.

Bibliography

Clinton, W. D. (1994). The Two Faces of National Interest. Baton Rouge: Louisana State University Press.

Foucault, M. (1996). Foucault Live: Interviews, 1966-84 (S. Lotringer, Ed.). New York: Semiotext(e).

Grainge, P. (2003). Introduction. In P.Grainge (Ed.), Memory and popular film (pp.1-20). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Hope, W. (2005). Giuseppe Tornatore: Nostalgia; Emotion; Cognition. In W. Hope (Ed.), Italian Cinema New Directions, (pp.53-78). Bern: Peter Lang Publishers.

Laviosa, F. (2005). Francesca Archibugi: Families and Life Apprenticeship. In W. Hope (Ed.), Italian Cinema New Directions, (pp.201-228). Bern: Peter Lang Publishers.

Marcus, M. (2002). After Fellini, National Cinema in the Postmodern Age. London: The John Hopkins University Press.

Marcus, M. (2007). Italian Film in the shadow of Auschwitz. London: University of Toronto.

Shaw, D. (2003). Contemporary Cinema of Latin American: Ten Key Films. New York, London: Continuum.

Storey, J. (2003). The Ariticulation of Memory and Desire: from Vietnam to the war in the Persian Gulf. In P. Grainge (Ed.) Memory and Popular Film (pp. 99-119). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Turim, M. (1989). Flashbacks in Film, Memory and History. London: Routledge.

Wood, M. (2005) Italian Cinema. London: Berg Publishers.

Filmography

Justiniano, G. (Director). (1994). Amnesia [Motion Picture]. Chile: Arca.

Özpetek, F. (Director). (2004). La Finestra di Fronte [Motion Picture]. Italy/Great Britain/Turkey/Portugal: R&C Produzioni/Redwave Films/AFS Film/Clap Filmes/Eurimages Conseil de l'Europe/Mikado Film Srl/Celluloïd Dreams

Monday, 5 July 2010

Smells

Sunday, 6 June 2010

Sally Potter